Theodor Wonja Michael was born in Berlin in January 1925. He was the youngest of four children of the Cameroonian colonial migrant Theophilus Wonja Michael and his German wife Martha, who originated from Posen (Poznań). When he was one year old, his mother died of a severe illness. Out of economic need, his father joined with all his children the Völkerschau (ethnological exposition) of Mohamed ben Ahmed, which used to be hired mainly by German travelling circuses like Holzmüller and Jakob Busch. From childhood on, Theodor and his three siblings Christiane, James, and Juliana had to play with their father the roles of “wild exotics”, as they corresponded to the fantasy of most Europeans at that time. From time to time, they also performed in feature films in the same functions. In his memoirs, Theodor Michael gives an impression of the degrading treatment by the visitors of such ethnological expositions: “My every move was stared at, total strangers ran their fingers through my hair, sniffed at me to see if I was authentic, talked to me in broken German and sign language, assuming I wouldn’t understand.” On the other hand, it was exciting for him to travel from place to place during the season. The youth welfare office, however, took this as an occasion to withdraw the father’s custody of the children and place them in foster families. The fact that Theodor and Juliana Michael ended up with Ben Ahmed via detours, while the two older siblings joined travelling artist groups, led the justification of the authority ad absurdum. From then on Theodor and Juliana not only had to continue to perform, but they also had to work in the household of “uncle” Mohamed’s family.

Standing, third from right: Theopilus Michael; seated in the middle with a turban: Mohamed

ben Ahmed, with Theodor Michael, aged three, on his lap, Christiane seated on the left, Juliana seated on the right, probably 1928 (Photo: Private Archive of Theodor Michael, Cologne, DTV).

Following the takeover of power by the Nazis in 1933, the older siblings Christiane and James emigrated with their circus groups to France, while Theodor and Juliana stayed with ben Ahmed, who had nothing to fear thanks to his Spanish-Moroccan citizenship. With the death of their father in 1934, the two siblings lost their last family support. As the demand for ethnological expositions decreased in Germany, several summer tours abroad followed until the beginning of the war, including Belgium, Poland, Scandinavia, and Romania. For business reasons, ben Ahmed presented his group members as “Ethiopians” during the Sweden tour in 1937, since after the Italo-Abyssinian War the Swedish sympathies were clearly with the suppressed Africans. Several Swedish families offered to take Theodor and Juliana into their home in order to save them from the racial policy of the Nazis, but ben Ahmed refused the offer, probably because he was afraid of the reaction of the German authorities. When Juliana was able to move to her older sister in France with the permission of the youth welfare office in autumn 1937, Theodor stayed behind alone.

Like other circus children, Theodor Michael attended school only irregularly. Nevertheless, he was a successful pupil and widely accepted in his Berlin school class. First hostilities appeared only after the Hitler Youth organization Deutsches Jungvolk (German Youngsters) had rejected him because of his skin colour. Thanks to his school achievements Theodor Michael received the permission to attend the Kant Gymnasium, but shortly afterwards he was expelled on the basis of “new regulations” and transferred to a general school of lower secondary education. The constant multiple stress and psychological insults finally left their mark. Theodor showed a retarded physical growth, suffered from permanent headache, and began to stutter. At the age of just fourteen he even suffered from gastric ulcers, which astonished the medical doctors.

After finishing school, Theodor Michael applied for an apprenticeship as a craftsman, but as a “non-Aryan” applicant he was rejected everywhere. In spring 1940, he found a job as bellboy at the famous hotel “Excelsior”. After some weeks the hotel management urged him to apply for a membership of the Deutsche Arbeitsfront (German Labour Front), the Nazi organisation that had replaced the former independent trade unions in Germany. The application led to a summons to the Reich Main Security Office. Although the conversation at the Security Police took place in an unexpectedly friendly atmosphere, it finally led to his early dismissal from the bellboy job, since Theodor Michael could not become a member of the German Labour Front because of his “negroid descent”. Shortly after he had more luck at the hotel “Alhambra”, which handled the official employment guidelines more relaxed. From time to time the new bellboy was even allowed to substitute the porter.

A welcome break from the oppressive everyday life were the occasional engagements as extra in movie productions. The German Federal Archives hold an index card of the Reich Chamber of Culture, on which is noted that Theodor Michael received 500 Reichsmark for his extra role as “negro boy” in the movie “Vom Schicksal verweht” (Gone with the Fate; directed by Nunzio Malasomma), which was shot in Italy in 1941. Most likely, the money was withheld by Theodor’s legal guardian ben Ahmed, who himself received 560 Reichsmark for his role. The peak of Theodor Michael’s ‘film career’ was the extra role as “fan-holder of the sultan” in Ufa’s large-scale production “Munchhausen” (directed by Josef von Báky), which celebrated its premiere in March 1943.

Theodor’s situation worsened dramatically when he had to undergo the physical examination for the military service in 1943. The Wehrmacht rejected him as “unworthy for military service”, after which the employment office declared him “liable for war service” at the J. Gast company in Berlin-Lichtenberg and sent him to live in the “Adlergestell camp for foreign labourers” in Berlin-Adlershof. Weakened by poor nutrition in the camp, he and the other forced labourers had to go to Lichtenberg every day and work up to twelve hours screwing iron parts together. Later he was assigned as electric cart driver, which meant a certain easing for him. Finally, the camp was liberated by the Red Army in April 1945.

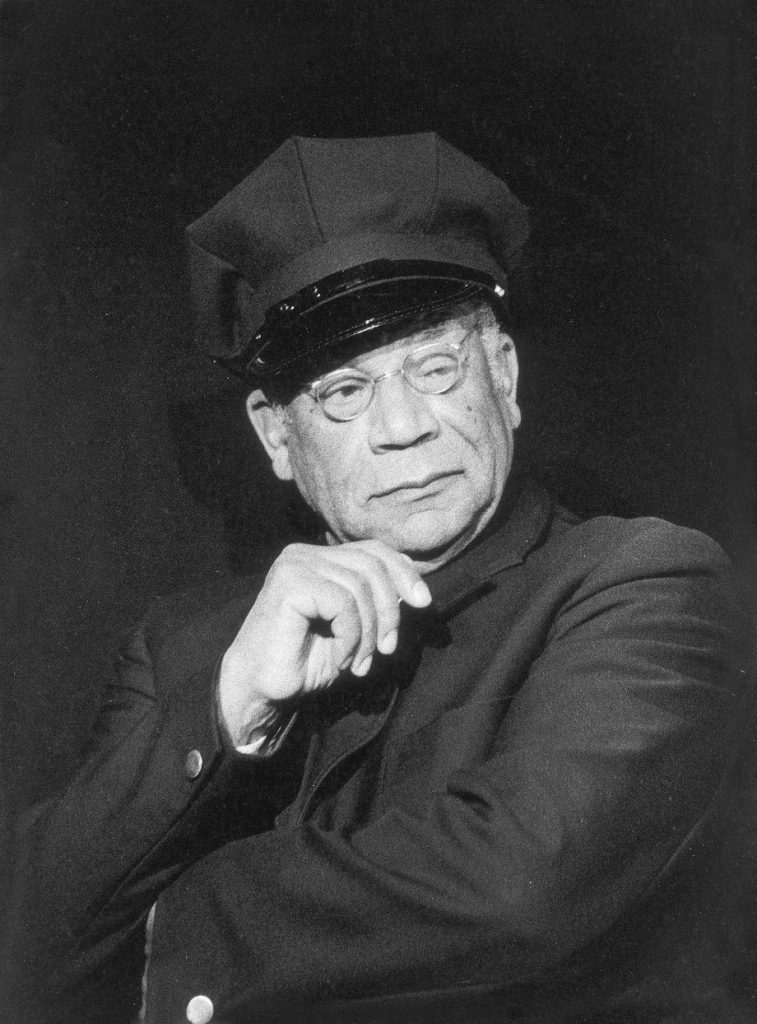

(Photo: Martin Holler).

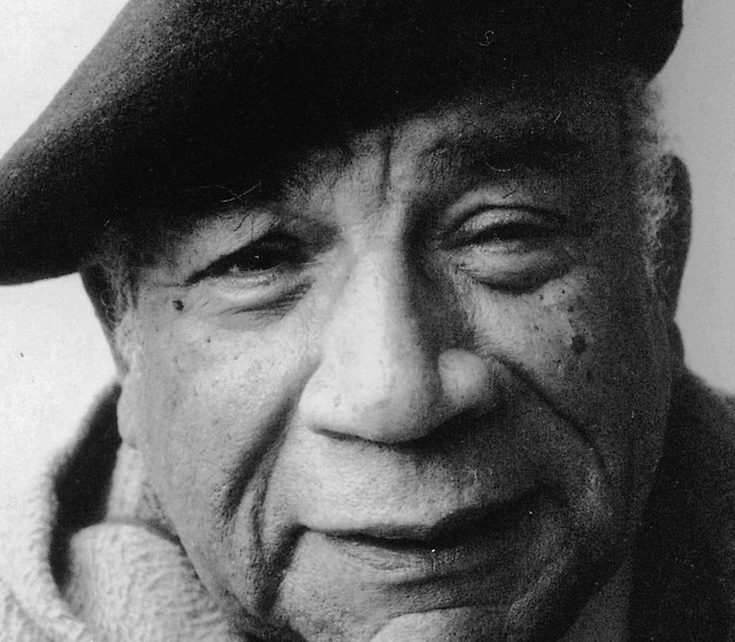

Soon after his liberation, Theodor Michael moved to Hesse, which was part of the American zone of Allied-occupied Germany. Through the contact with Afro-American soldiers he learnt to speak English so well that he was able to work for the US Army as an interpreter for a while. He abandoned his plans to emigrate to America after experiencing the American “racial segregation” at first hand: While some white US soldiers treated him with condescension because of his skin colour, he was denied access to dance nights and other events. In 1947, Theodor Michael married the nurse Elfriede Franke from Silesia and started a family. It was difficult for him, however, to find sufficiently paid work to secure the livelihood. Since he had no certificates of qualification to show, he had to get by with odd jobs like small roles in theatre, television, and radio dramas, but also collecting metal. In 1956 he fell ill with severe pulmonary tuberculosis, which took three years to heal completely. Afterwards his fate finally changed for the better. As a member of the German Stage Cooperative it was possible for him to study two years at the Hamburg Academy of Social Economy and to add one year as a guest student in Paris, where he became acquainted with the French scientific literature on Africa. After his return to Germany he worked as an expert on African questions for several economic journals and finally became the managing editor of the newly founded “Afrika-Bulletin” in Cologne. At the end of 1971, Theodor Michael followed an invitation of the Bundesnachrichtendienst (Federal Intelligence Service of Germany), where he could work as a specialist on Africa in the rank of a councillor. After his retirement in 1987 he returned to the stage, but this time not out of economic pressure, but out of pure love for theatre. Furthermore, he became a member of the Initiative Schwarze Deutsche (Initiative of Black People in Germany – ISD), since the everyday racism in Germany accompanied him throughout his life despite his personal success. In retrospect, he complained that the “small grass skirt of the ethnological exposition” had always followed him. Thoughtfully he asked himself in advanced age: “When will my grandchildren finally be judged by their character and not by the colour of their skin?” In 2018, Theodor Michael was awarded the German Bundesverdienstkreuz (Federal Cross of Merit) for his social engagement as a contemporary witness to history. One year later, in October 2019, he died in Cologne.

Author: Martin Holler

Sources:

Interview with Theodor Wonja Michael, Cologne, 7 December 2018.

Federal Archives Berlin-Lichterfelde, R 9361-V/123765 and R 9361-V/134277; Lewerenz, Susann: Geteilte Welten. Exotisierte Unterhaltung und Artist*innen of Color in Deutschland 1920-1960. Cologne 2017; Michael, Theodor: Deutsch sein und schwarz dazu. Erinnerungen eines Afro-Deutschen. Munich 2013 [English version: Michael, Theodor: Black German. An Afro-German Life in the Twentieth Century. Liverpool 2017]; Reed-Anderson, Paulette: Rewriting the Footnotes. Berlin und die afrikanische Diaspora – Berlin and the African Diaspora. Berlin 2000.

Featured Image (above): Autograph card, 2000. Private Archive of Theodor Michael, Cologne; DTV.