The transcript of the escape story of the Schauerjans family is the result of a collaboration between descendants of the circus family and the French historian Laurence Prempain.

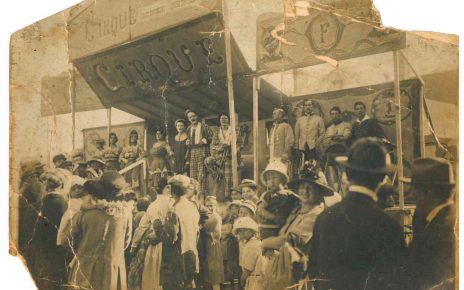

Until 1943, Rosa (born 1902) and François Jacob Schauerjans (1903) lived with their children Edwige (born 1928) and Roger (born 1938) in Grenoble, France. Two versions of their escape story to Switzerland continue to circulate among the descendants Dutch circus family. According to a narrative remembered by Laura Cassagne, Rosa’s grandniece, Rosa ran a small cabaret in a shop. In those days, the Germans were looking for artists to entertain Wehrmacht units. Unwilling to take part in such tasks, Rosa and her husband decided to flee to Switzerland. Together with their children, the couple crossed the border through a river. Upon their arrival in Switzerland, they were soon able to resume their circus activities.

Rosa’s nephew Maurice Argentier recalls another legend: “I’ve heard, when the Germans arrived in Grenoble in 1943, they wanted to arrest the Schauerjans’ family”. According to him, Rosa or her mother Julie had vigorously protested and submitted official papers stating that they were Dutch citizens. The nephew also pointed out that the Germans would have suspected Rosa’s husband of being a Jew, because his first name was Jacob.

The historical background for Argentier’s story: After the Allies landed in North Africa on 7/8 November 1942, Grenoble fell under Italian control. The Italian forces granted the Jews a certain degree of protection. For this reason, the Jews considered Grenoble as a safe haven at that time. After Italy switched sides in September 1943, Grenoble was immediately occupied by German troops.

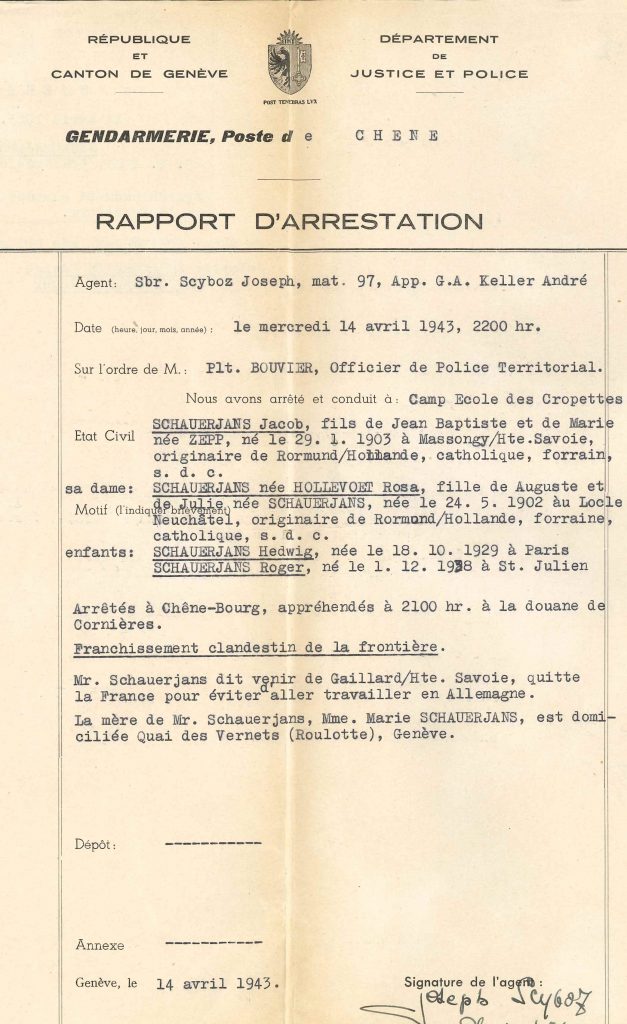

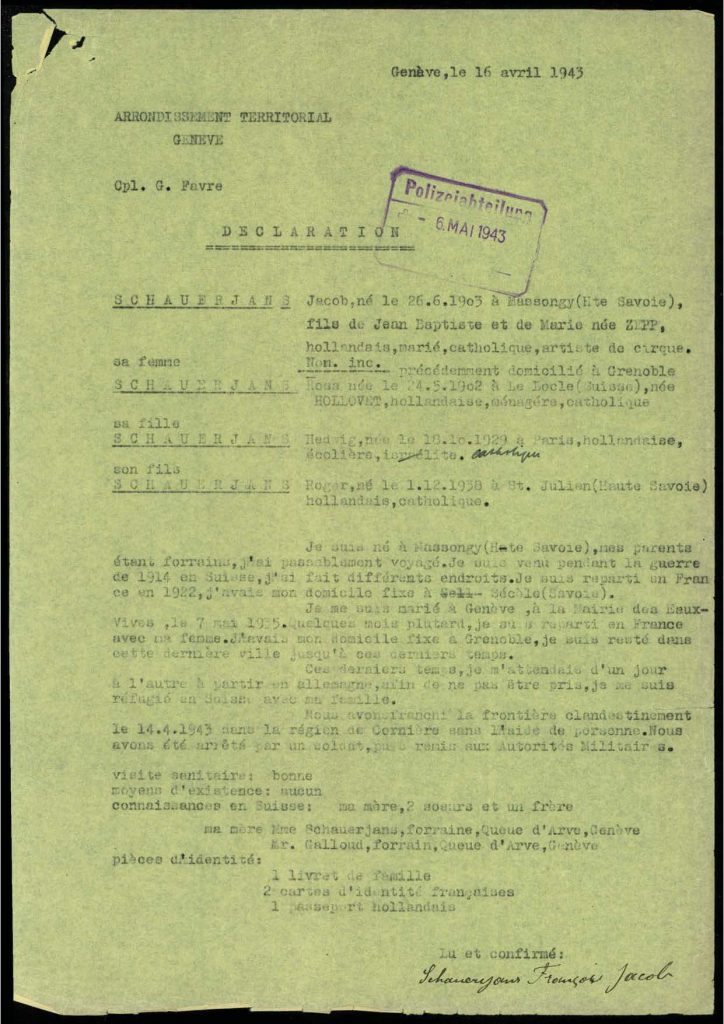

A Swiss government document stored at the Federal Archives in Geneva provides a reference to a third, probably actual motive, for the escape of Schauerjans. A police account reports the family’s border crossing and immediate arrest of all four family members on Wednesday evening, 14 April 1943. According to the records of the officer in charge, the father’s motive for the escape was to avoid compulsory labour in Germany: “Mr. Schauerjans […], quitte la France pour éviter d’all travailler en Allemagne”.

The common thread in all the narratives was the identification of the National Socialist rule as both a threat to the family’s life and a motive for the escape.

Combination of various security strategies

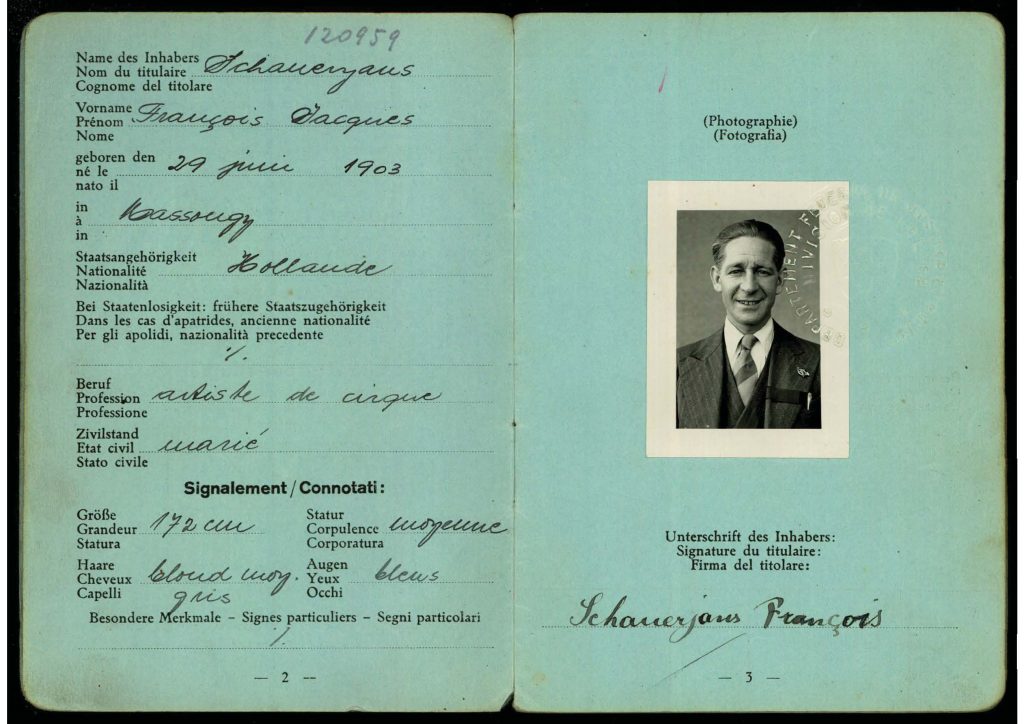

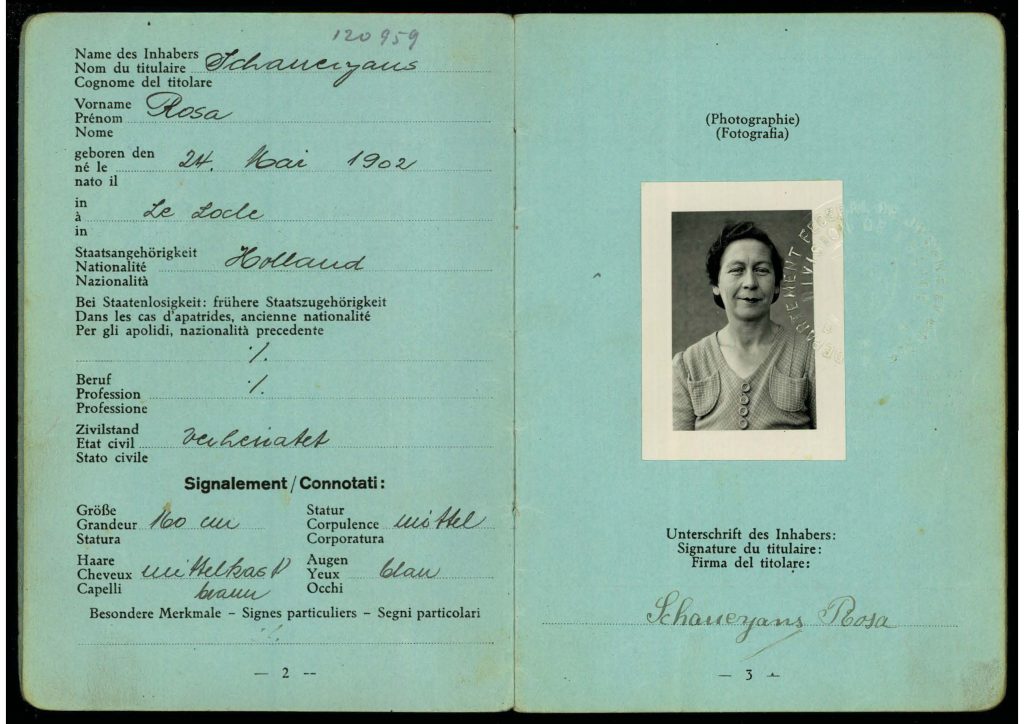

Switzerland set high hurdles for legal entry of those seeking refuge in the country. The Swiss Federal Police endeavored to keep the number of refugees as low as possible. Officials were instructed to focus on “particularly valuable people” and to favour those with close ties to Switzerland and sufficient financial resources. The Schauerjans family did not fulfill these criteria. However, until 29 December 1942, families with children under the age of 16 and men between the ages of 18 and 50 who were on draft lists for the labour force in Nazi Germany could hope for exile in Switzerland. Likewise, persons who could prove the existence of family ties in Switzerland had better chances for legal admission. Thereafter, the admission regulation were tightened up. In this situation it was advantageous for the Schauerjans family that the Dutch government in exile in London and the Swiss government had negotiated an agreement allowing Dutch citizens to enter Switzerland.

After the border crossing of the family on the evening of 14 April 1943, François Jacob used various security strategies when interrogated by the Swiss border guards to increase the admission chances of all family members in Switzerland. To the border officials, the father stated that all family members are Dutch citizens, hailing from Roermond. In fact, all four family members held Dutch passports that had been issued by the Consulate in Lyon on 29 July 1942.

Source: Geneva State Archives, Justice and Police Ef 2284.

With Dutch citizenship, the family could appeal to the Dutch-Swiss refugee agreement. In addition, the family used further strategies to secure its admission: for example, François Jacob declared that his wife Rosa was born in the Swiss town of Le Locle. In order to take advantage of the situation of their 13-year-old daughter Edwige, he explained that she was “Israelite” in her religious denomination. All other family members were declared as “Catholic” in the interrogation account. François Jacob also told the police that his mother, Marie Schauerjans, as well as his brothers and sisters, were still living in the city of Geneva. Finally, he expressed the fear that he would be sent to take part in the German labour force.

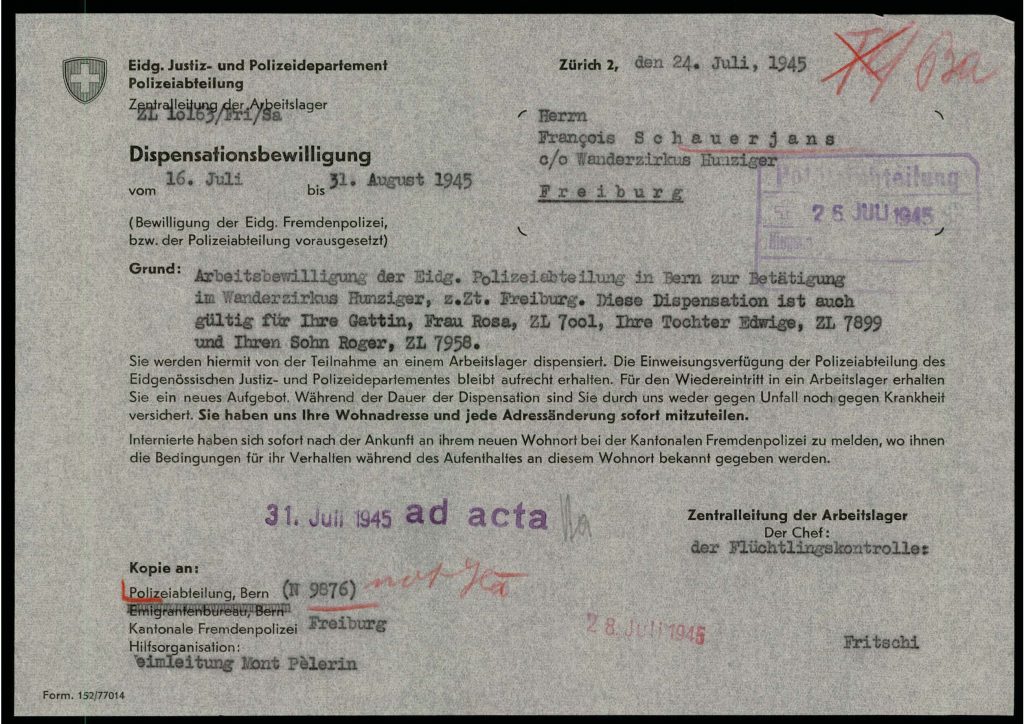

The family had to go to an internment camp, even hough the grandmother Marie Schauerjans offered that all family members could live in her home and that she would pay for their upkeep. On 11 May 1943, the Swiss authorities gave the children permission to move in with their grandmother. The parents, however, remained in separate camps. Finally, the family was reunited in the Mont Pélerin camp in December 1943 due to the grandmother’s illness. In this camp the family stayed until 27 July 1945.

Starting to work again

In two short periods, from 27 July to 24 August 1943 and from 15 May to 24 June 1944, François Jacob was able to earn money outside the camp as an agriculture worker. After the war, the family wanted to work in the fairground business together with Marie Schauerjans. However, the Swiss Federal Office of Industry, commerce and labour rejected their application due to the difficulties faced by the fairground market after the war.

Source: Geneva State Archives, Justice and Police Ef 2284.

Temporary show employments for the whole family made it possible to leave the camp. Among others venues, the family performed at the Arènes Variétés Nationales in the canton of Friborg. On 24 September 1945, Marie Schauerjans was authorized by the Federal Office to hire her son along with his family at her fairground business. Although, the family was still under police control, they were permitted to settle in a caravan at a private place in Lausanne. Unfortunately, the family struggled with bad hygienic conditions, which probably caused Roger to contract tuberculosis. In April 1948, the Swiss authorities informed the family that they all could stay in Switzerland.

Author: Laurence Prempain

Sources: Spuhler, Gregor (Ed.): Independent Commission of Experts Switzerland – Second World War: Switzerland and Refugees in the Nazi Era, Bern, 1999; Swiss Federal Archives, Bern. Federal Department of Justice and Police, Handakten Heinrich Rothmund, File 195. Bericht über die Einreisepraxis des Emigrantenbureaus der eidg. Fremdenpolizei [Report on the Entry Procedures of the Immigration Office of the Federal Police for Foreigners], October 12, 1942; Swiss Federal Archives, Bern. Federal Department of Justice and Police, Niederlassungsangelegenheiten von Ausländern, Aus- und Wegweisungen, Ausweisschriften für Flüchtlinge, Internierungen, 1904-2018. Francois Jacob, Edwige, Roger, Pierre and Rosa Schauerjans, Files 15111, 15112, 15113, 15114, 15115; Geneva State Archives, Justice and Police. Schauerjans, Ef 2.2844; Family collections and personal memories from Laura Cassagne, Anne-Marie and Maurice Argentier.